The biodiversity of temporary ponds

Coping with drought

Many organisms don’t mind that ponds dry out. In fact, a substantial diversity aquatic organisms can only thrive in ponds that regularly or at least occasionally dry out. In general, temporary pond species use different strategies to survive in temporary ponds. Many have drought resistant life stages in the form of encysted embryos (resting eggs) or other cryptobiotic life stages such as larvae or adults encased in protective capsules of mucus. These allow populations to bridge the dry period in situ. Some examples of dormant life stages of temporary pond organisms are provided below.

Large branchiopods

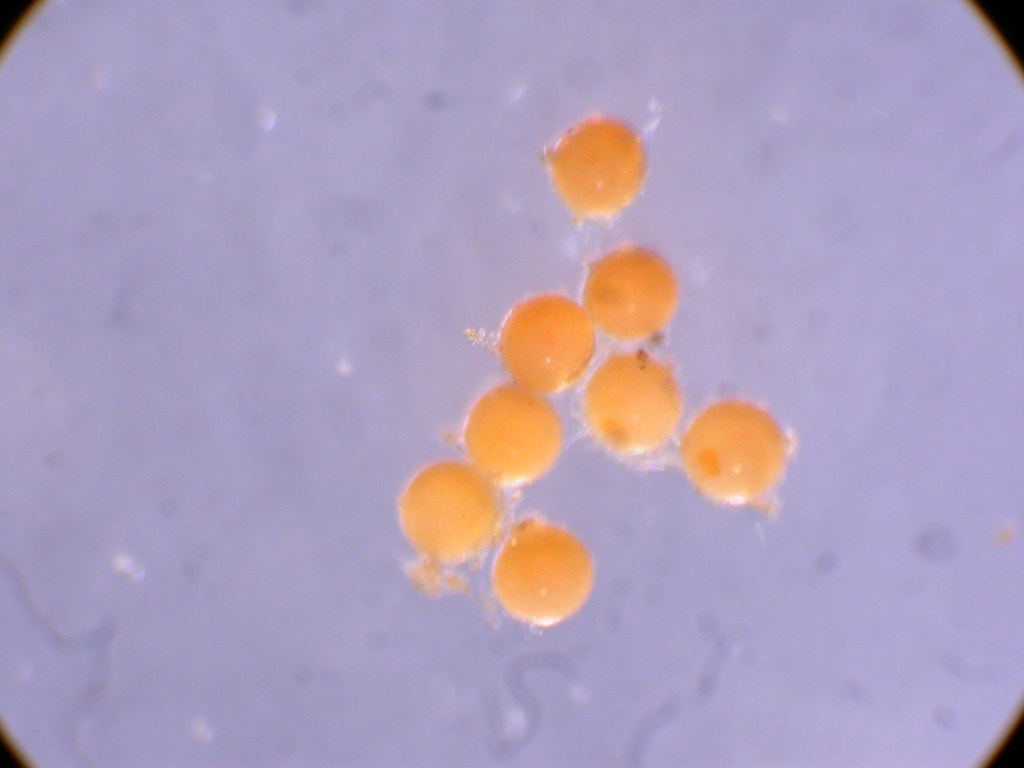

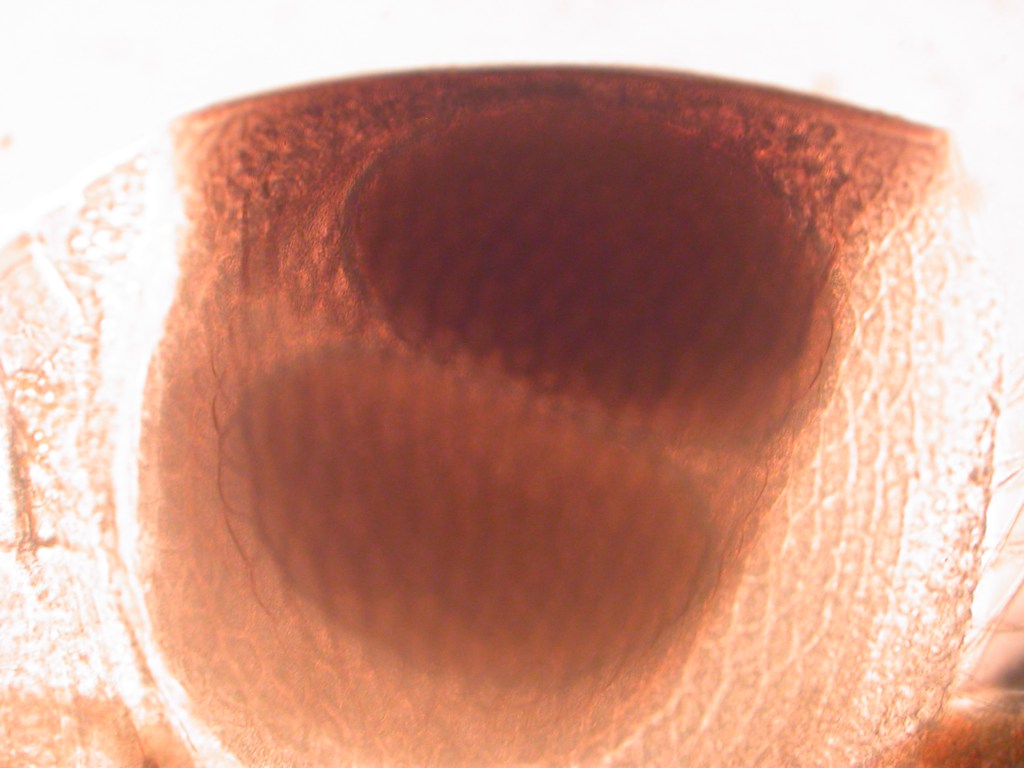

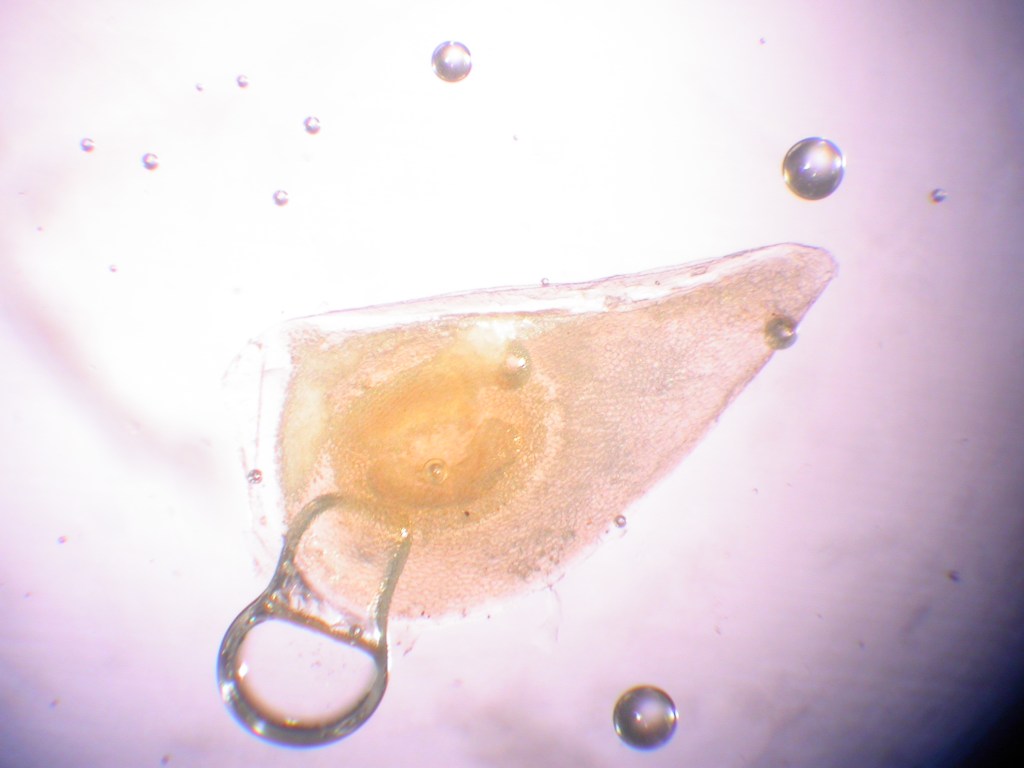

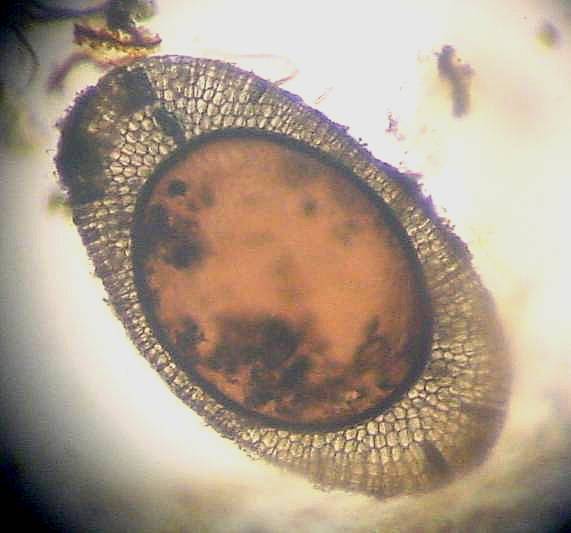

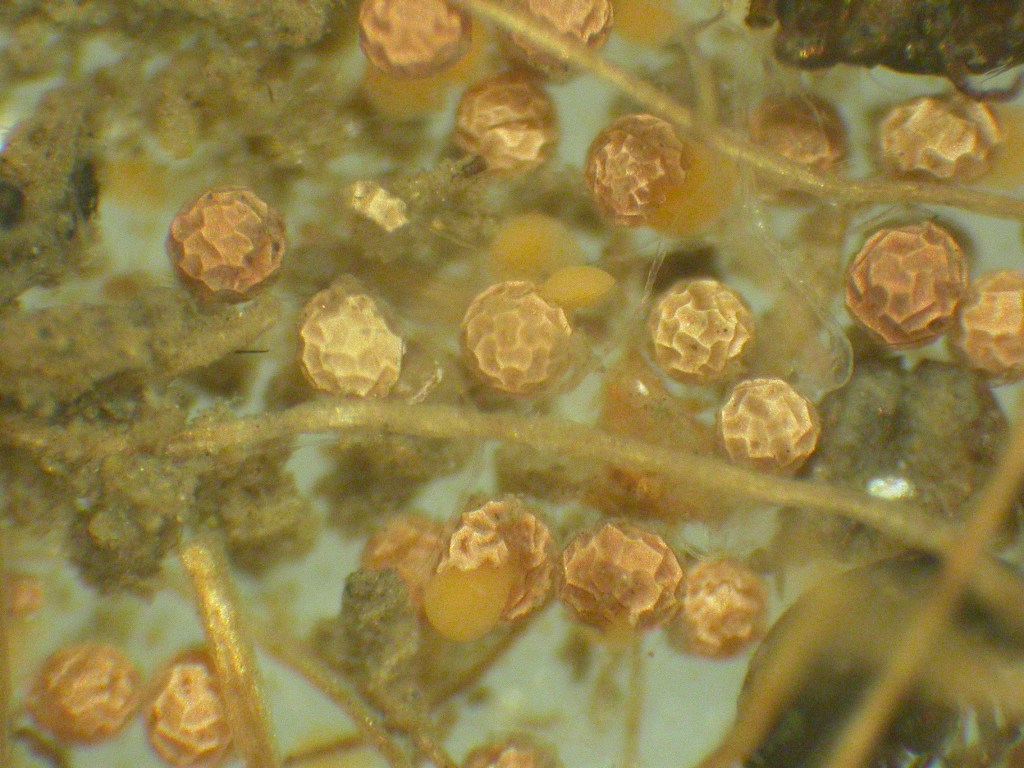

The most typical elements of the fauna of temporary ponds are large branchiopod crustaceans. These organisms have existed in temporary ponds since the Devonian more than 350 million years ago and are almost completely restricted to the habitat. They are found in permanent salt lakes and very rarely appear in a permanent mountain lakes or arctic lakes where fish predation is low or absent. All produce dormant resting eggs (encysted embryos) that help them to bridge the dry period. The three main surviving groups are the fairy shrimps (Anostraca) that lack protective shells, the clam shrimp (Spinicaudata, Laevicaedata & Cyclestherida) encased in two lateral shells and the tadpole shrimp (Notostraca) that have a dorsal protective shell. Fairy shrimp and the closely related brine shrimp (Artemia spp.) are pelagic filter feeders that swim on their backs. While the paired legs are used for filtering, breathing and swimming, the long abdomen with its forked abdomen can be used as a dolphin’s tail for rapid evasive maneuvres e.g. to avoid predators. Clam shrimp are better protected against predator and filter feed from within their protective valves. Sometimes they swim actively, other species like to burry in the sediment. Tadpole shrimp are globally represented by only two genera: Triops and Lepidurus with the latter being more common in colder climates. They are important predators in temporary waters that catch prey using modified leggs fitted with spiny attachments. Many hunt at night when they are less likely to be spotted by visual predators such as storks and spoonbills.

Passive vs. active dispersers

Most organisms with effective dormant life stages are crustaceans, rotifers and worms. They are passive dispersers that rely on vectors such as water, wind and adherence to mobile animals to disperse to new ponds. In turn, the insects and amphibians that thrive in temporary ponds are active dispersers that use different habitat cues to select in which pools they will reproduce. Amphibians and many aquatic insects have mobile adults that visit temporary ponds to lay eggs or deposit larvae but leave (or die) when the ponds dry out. These adults may survive in the terrestrial habitat matrix (in the case of amphibians) or move to more permanent aquatic habitats in the region (in the case of some water beetles and bugs).Wiggins and coworkers (1980) recognised that there are also survival strategies that capture a bit of both. Sometimes mobile organisms such as certain chironomids, odonates and beetles may colonize a temporary pond (either at the start or later during the inundation) but at least a portion of the eggs, larvae or adults have the ability to also persist in situ through the dry period e.g. in the form of a cryptobiotic life stage or by hiding in wet mud or a a protective coccoon. Another interesting mix of a mobile coloniser combined with a resistant life stage is found in Aedes mosquitoes. Here the adult female lays drought resistant eggs in dry pool basins before the water arrives.

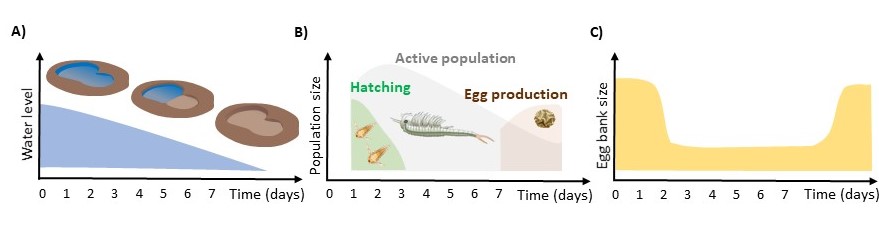

The figure below shows the life cycle of a typical temporary pond organism that uses resting eggs to bridge dry periods. The fairy shrimp Branchipodopsis wolfi from temporary ponds in Southern Africa. Resting eggs hatch from the sediment in the first 24 hours after inundation and this is stimulated by low conductivity and low temperatures. The larvae grow fast and when they are not limited too much by the high density of conspecifics they can reach maturity and start to produce their own resting eggs after just 7 days. Tom Pinceel and coworkers recently shed light on the complexity of this mechanism. Not all eggs hatch during each inundation, ensuring that at least a fraction remains dormant in the sediment. In case the pond would dry out before the fairy shrimp can reproduce, this prevents local extinction of the population

A life without fish

Although permanent ponds can differ from permanent ponds in many aspects, the most crucial difference is that fish tend to be absent from temporary ponds and therefore temporary pond species generally don’t suffer much from fish predation. As a result, temporary pond zooplankton can be much larger than in permanent ponds with fish and insect predators can be quite diverse and abundant. Sometimes fish can end up in temporary ponds when they are transported there e.g. when ponds connect with rivers or permanent ponds. In Africa adventurous fish such as Clarias gariepinus catfish can move overland to temporary ponds during rainy nights. Finally, a very select club of fish are uniquely adapted to the temporary pond environment and can survive the dry periods in slime coccoons (e.g. African lungfish) or as dormant embryos in the sediment (African killifish of the genus Nothobranchius). Temporary ponds house populations of typical boom-and-bust organisms (e.g. fairy shrimp) that profit from the abundance of resources at the start of an inundation, grow very fast and mature before the pond eventually dries out or before predators reach high densities.

Despite the typical absence of fish, temporary ponds are certainly not enemy-free. Water beetles, and bugs typically thrive and so do several damselflies and dragonflies. Below are some water beetles from the temporary ponds in Doñana, Spain by A. Portheault. From left to right: Eretes griseus, Helochares lividus, Colymbetes fuscus and Hygrobia hermanni.

Besides beetles, temporary ponds can house many different species of dragonflies and damselflies as well as a number of water bugs including water boatmen, backswimmers and water scorpions. In parts of Africa, sometimes fishing spiders (e.g. of the genus Nilus) can be found in temporary ponds.

Temporary ponds are the preferential breeding habitats of many amphibians including threatened species. They benefit from the warm shallow water conditions and lack of large fish predators.